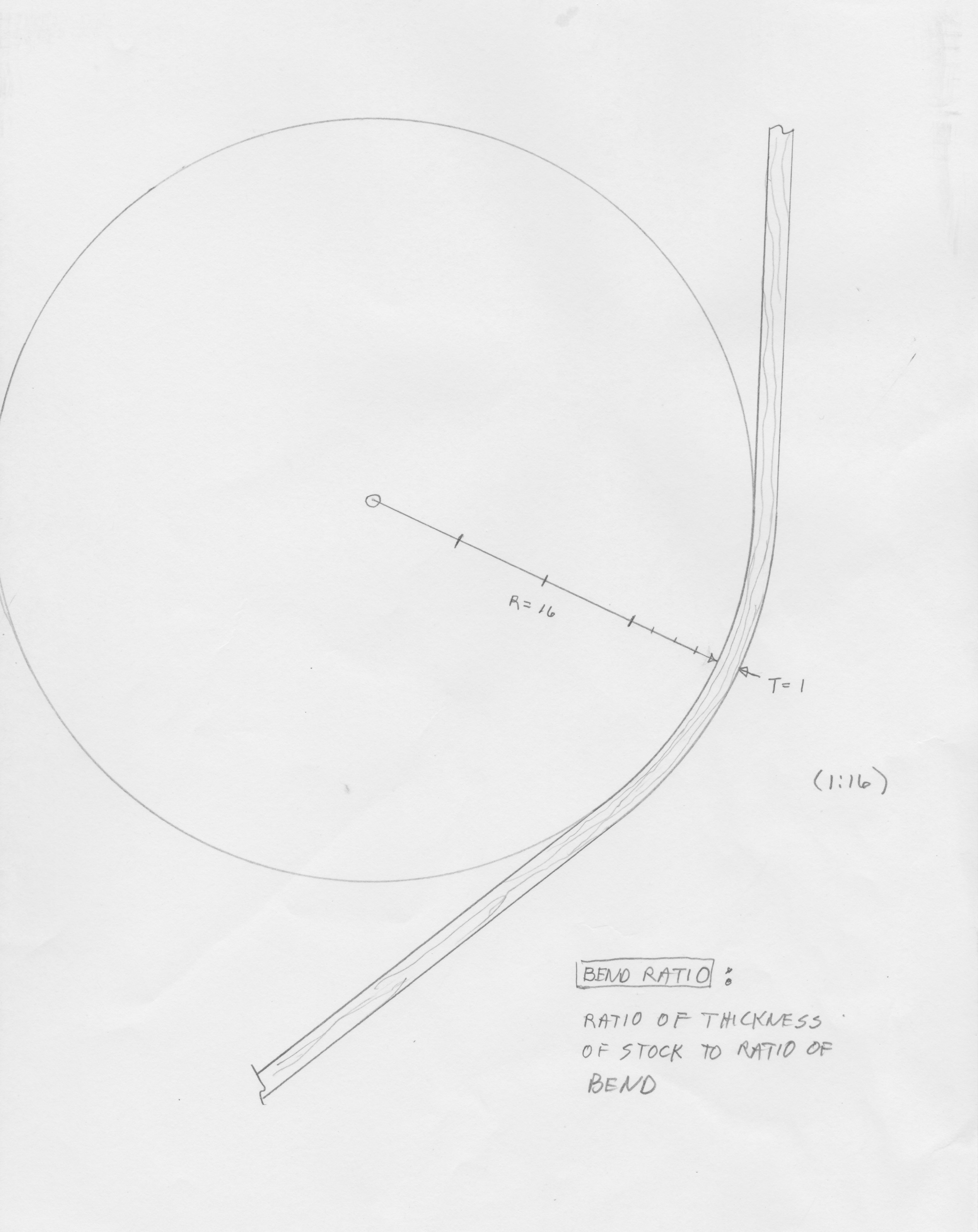

This sketch shows an old boatbuilding scheme for figuring out how tight (used to be called “quick”) a certain thickness of wood will bend. (The wood is usually steamed to temporarily loosen up the lignin bonding the grain fibers). The rule of thumb* states that the workpiece be at no thicker than one-sixteenth the radius of the bend. To be safe, and for most species, its best to not exceed one-fourteenth.

By making a drawing to full scale as illustrated here, you can lift a direct measurement (“scantling” in boatbuilder lingo) of the wood to be bent. Start by making a circle to the radius of the desired bend; draw a radius line and divide it into sixteen segments. One of these segments represents the stock thickness.

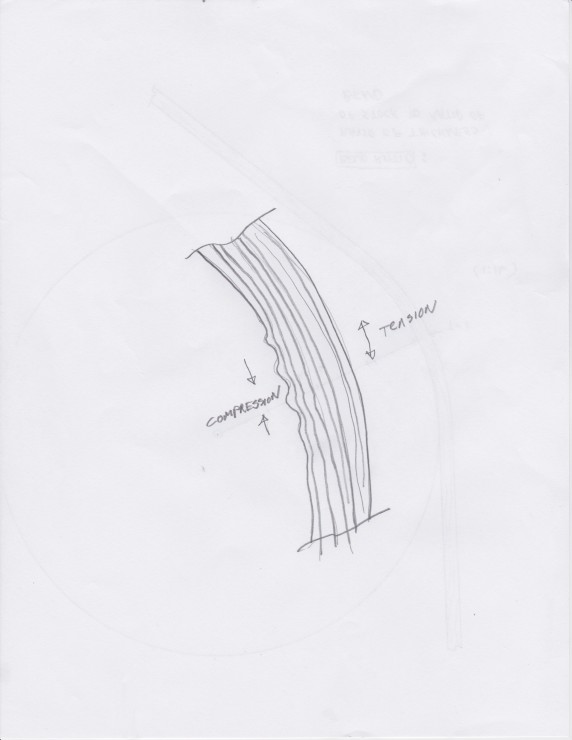

If the wood is too thick for the bend, the fibers on the inside of the curve compress and fold–and these folds increase the wood’s resistance to more compression. This, in turn, transfers the strain to the outside of the bend, putting too much tension on the fibers and permanently weakening them.

Usually the wood will break forcing you to replace it (and you actually will want it to if strength is a primary consideration). To increase your chances of success you can make the steam a little wetter; you can change the grain orientation (some builders swear by making the rings parallel to the bending form–some swear it makes no difference) and (I vote for this) you can select wood from the upper portion of the tree where it has already spent its life bending in the wind).

Or, you can throw up your hands and just make the wood thinner. Of course, in the case of boat ribs which are critical to the integrity of the hull, this means you will need more ribs (at closer spacing) to make up for the loss of strength per rib.

*Rule of Thumb credit goes to an article by Ed McClare in WoodenBoat Magazine #126. Highly recommended reading for more info on the properties of wood under bending stresses.

Jim Tolpin

5 thoughts on “Going ‘Round the Bend”

mbholden

This is a common measurement in sheet metal bending. The shortcut is: xT where x is the radius of the bend expressed in multiples of the thickness of metal. Steel suppliers offer minimum xT for their steels to help designers pick the proper alloy for their designs, or conversely, change their design to meet the requirements of the alloy.

momist

So useful! Thanks for posting this – it’s not easy to find this type of knowledge.

Tyler Broom

I’m confused. It says that 1:16 is the limit but wouldn’t 1:14 be an even tighter bend? I may just be visualizing it wrong.

Tyler

Jim Tolpin

Tyler: Picture it this way: if the radius is 16″, then one-sixteenth of this radius would be one inch–the thickness you would make the wood to take this bend safely. If you were to make the thickness one-twelfth of the radius, it would be 1/12 of 16 or 1 1/3 inches thick….which according to the rule would compromise its long-term strength as the fibers would be overly tensioned on the outside of the bend.

jwaldron

Wait! Wait! Thinner and more numerous frames isn’t the only answer. There are also laminated frames, which have indeed many advantages over steam bent solid frames even if breakage isn’t the big issue. With good epoxy resins, laminated frames can be stronger than solid frames.

The rule is still useful, of course, to determine the greatest appropriate thickness of each individual ply in a laminated frame. Don’t want to waste a lot of energy (or for those so inclined, a lot of electrons) cutting more and thinner plies than needed.